Obtain Vibration Mode Using GPS Technology

Abstract | Download Paper

To measure the vibration modes of large structures, such as dams, buildings, bridges, tunnels, ships, or aircraft, high-channel-count data acquisition systems are commonly employed before. These systems capture vibration signals, which are then subjected to modal analysis. However, this traditional approach faces challenges related to the fixed location of the data acquisition systems and the extensive cabling required to position sensors throughout the structure. Such setups are often cumbersome and costly, particularly when measuring hundreds of channels in response to ambient excitations such as wind or pedestrian traffic.

Leveraging satellite-based Global Positioning System (GPS) technology, Crystal Instruments has developed an innovative method that uses as few as two portable data acquisition systems to capture vibration data, replacing the need for high-channel-count systems. This method enables precise synchronization of data collected from multiple acquisition units without the need for physical wiring.

This paper presents findings from an experimental investigation employing this novel approach to identify the frequency signatures of a building under ambient excitations. The results demonstrate that this method effectively analyzes the dynamic properties of the structure, offering a promising solution for structural health monitoring applications.

Keywords: Operational Modal Analysis, Building Vibration, GPS Technology, Dynamic Properties, Data Acquisition, Dynamic Signal Analysis

Introduction

Modal analysis is crucial in the field of structural dynamics, providing insights into a structure's response to vibrations and external forces. This method allows engineers to determine the modal properties (natural frequencies, damping ratios, and mode shapes), which are essential for understanding how a structure behaves under operational conditions and potential environmental stresses.

Fig. 1 Modal parameters identified through modal analysis

Modal analysis has evolved over decades from basic free vibration tests to sophisticated techniques involving forced vibration and ambient excitations. The use of digital technology revolutionized the field, leading to the development of tools capable of performing operational modal analysis (OMA) without needing artificial excitation. Traditional setups were constrained by extensive wiring, fixed sensor placements, and difficulties with data synchronization. The emergence of distributed systems coupled with GPS synchronization represents a significant leap in simplifying these processes and enhancing accuracy.

Fig. 2 Innovative approach of distributed systems with patented GPS timestamp technology

Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) relies on continuous or periodic monitoring of a structure's dynamic properties to detect any changes that might indicate damage or degradation. Variations in natural frequencies and damping ratios can signal issues such as cracks, joint loosening, or material fatigue.

Fig.3 Advancing Structural Health Monitoring of structures

Consider a large public building designed to withstand seismic activity. Regular OMA can identify shifts in its modal parameters, signaling potential weakening long before visible signs of damage appear.

Fig.4 Monitoring shift in natural frequencies to detect structural changes

Therefore, OMA provides a non-destructive means of assessing structural integrity over time.

Motivation

In traditional OMA, fixed sensors are deployed across a structure, connected by extensive cabling to a central data acquisition system. This method presents several challenges:

Logistical Complexities: Deploying and managing cables in large structures (e.g., high-rise buildings or bridges) is time-consuming and expensive.

Data Synchronization Issues: Misalignment of data due to varying cable lengths and transmission delays can compromise analysis accuracy.

Sensor Placement Limitations: Fixed locations limit coverage and flexibility, potentially missing key vibration nodes.

Fig.5 Cabling issues with traditional approach

The integration of distributed handheld systems such as the CoCo-80X, equipped with GPS timestamp technology, addresses these challenges by providing an innovative solution. GPS synchronization ensures data collected from multiple devices is precisely aligned, even if the devices are not physically connected. This method allows for flexible sensor deployment, easier installation, and reliable data acquisition across large areas.

Fig.6 Distributed handheld analyzers for new approach of OMA

The system comprises the CoCo-80X handheld device—known for its rugged design and advanced capabilities such as 8-channel data collection, 20 V input, and a high dynamic range of 150 dBFS. Equipped with GPS antennas, the CoCo units synchronize timestamps, allowing collected data to be merged accurately post-recording. The approach leverages patented technology to correct sampling rates, ensuring time-domain signals are properly aligned before being processed into the frequency domain.

Fig.7 Patented GPS timestamp tech to synchronize signals from various data acquisition systems

The collected data is further refined using EDM Modal software, which extracts the modal parameters essential for structural analysis.

Theoretical Framework

The following theoretical approach outlines the comprehensive workflow for conducting operational modal analysis using distributed handheld systems equipped with GPS timestamp technology. This method begins with capturing raw acceleration data from strategically placed uni-axial accelerometers mounted on various points of a structure and ensuring precise time synchronization via GPS timestamps across all devices. The analog data is filtered using anti-aliasing and high-pass filters to remove unwanted frequency components and DC offsets. Following filtration, the signals are quantized and digitized using dual 24-bit ADCs. A Hanning window is applied to reduce spectral leakage.

Fig.8 Flowchart illustrating theoretical framework

The time-domain data is transformed into the frequency domain through a Discrete Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), with subsequent amplitude and energy correction to maintain data integrity. The Cross Power Spectrum (CPS) between reference and response signals is calculated, phase corrected, averaged, scaled, and smoothed to minimize noise. Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) on the CPS matrix produces the Complex Mode Indicator Function (CMIF), indicating the modes of the structure. Finally, the Poly-X method with the p-LSCF algorithm is used for curve-fitting the CMIF plots to extract modal parameters such as natural frequencies, damping ratios, and mode shapes providing comprehensive insights into the dynamic properties of the structure.

1. Record Measurements

The first crucial step in this operational modal analysis workflow is the meticulous recording of raw acceleration data. To achieve this, uni-axial accelerometers are strategically placed at pre-determined measurement points across the structure. This precise positioning ensures that the data collected accurately reflects the structure’s vibrational responses under ambient conditions. When multiple sensors need to be placed at the same location to capture multi-directional data, mounting blocks are employed to securely hold the accelerometers, maintaining their alignment and stability throughout the testing phase. The CoCo-80X handheld device is central to this process, renowned for its robustness and capacity for reliable data acquisition in the field. This device records the raw timestream data from the accelerometers, capturing high-resolution measurements essential for post-analysis. To apply the GPS time stamps to the data collected from multiple units, GPS antennas are integrated into the system to record timestamps, ensuring precise temporal alignment across all distributed CoCo-80X devices.

Fig.9 Recording raw timestream data from accelerometers on CoCo-80X

Anti-aliasing and high-pass filtering are essential signal processing steps that ensure the integrity of the data collected during operational modal analysis (OMA). These filtering techniques help prepare the raw acceleration signals for accurate analysis by removing unwanted noise and preventing distortion.

Fig.10 Diagram showing the attenuation of higher frequencies with Anti-Aliasing filter

The anti-aliasing filter is used to eliminate high-frequency components from a signal before it is sampled. This step is necessary to prevent aliasing, which occurs when high-frequency signals are under sampled and appear as lower-frequency components, distorting the actual signal.

Fig.11 Diagram showing the attenuation of lower frequencies with High-Pass filter

A high-pass filter is applied to remove low-frequency noise and DC (direct current) offsets from the signal, which can obscure meaningful vibrational data. This type of filter allows frequencies above a certain cutoff frequency to pass while attenuating lower frequencies.

Quantization and digitization are critical processes in converting analog signals into a digital format suitable for computational analysis ensuring that the recorded data accurately represents the real-world vibrations of a structure.

Fig.12 Diagram showing the quantization and digitization of random signals

Quantization is the process of mapping a continuous range of amplitude values in an analog signal to a finite set of discrete levels during conversion to a digital signal. This step introduces a finite precision that represents the signal with a limited number of bits.

Digitization follows quantization and involves converting the quantized signal into a binary format that can be processed and stored by digital systems. The digitized signal is represented as a sequence of binary numbers corresponding to the quantized amplitude levels.

The CoCo-80X system has a patented technology of dual 24-bit ADCs, allowing for high-resolution digitization. A 24-bit ADC provides 224 quantization levels, which translates to extremely fine granularity and minimal quantization error. This level of resolution is crucial in modal analysis, where capturing subtle variations in vibration data is essential for accurate analysis.

Fig.13 CoCo-80X system

The precision enabled by 24-bit ADCs allows for a dynamic range of approximately 150 dB, supporting the accurate capture of both low-amplitude and high-amplitude signals. This ensures that detailed information about the vibrational response of a structure is retained, facilitating a thorough frequency domain analysis through processes like Fast Fourier Transform (FFT).

An operational test setup typically involves using more than one CoCo-80X device to enable comprehensive data collection from different points on the structure. One device is strategically fixed at a designated location to serve as the reference point, consistently recording data from reference accelerometers that capture baseline vibrations. Meanwhile, additional CoCo-80X units are roved between different measurement locations, acquiring data from roving accelerometers that monitor variable points across the structure. This systematic approach, involving both fixed and roving sensors, allows for extensive coverage of the structure’s response characteristics. By employing GPS-enabled handheld devices, the procedure enhances the reliability of the data by ensuring that all measurements, regardless of their physical distance, are accurately timestamped and then synchronized.

Fig.14 The measurements recorded on all CoCo-80X systems

This enables seamless merging of data during post-processing, facilitating comprehensive analysis and the extraction of key modal parameters critical for assessing the structural integrity and dynamic behavior of the structure.

2. GPS Time Stamping

The patented GPS timestamp technology for synchronizing the acquired data is based on leveraging the precise timing provided by Global Positioning System (GPS) satellites. Each CoCo-80X incorporates a GPS receiver that captures timing signals from multiple satellites. These signals provide highly accurate timestamps—typically precise to within 100 nanoseconds—ensuring that each data point recorded by the unit is synchronized with Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). This embedded timestamp allows for seamless alignment and merging of data collected from different systems operating independently and potentially at significant distances apart.

A simplified diagram of how time stamping works in the CoCo is shown below:

Fig.15 Time stamping flowchart illustration

In the hardware, a time register is derived from the GPS receiver chip that is directly accessible by the FPGA and the processor. The GPS timing accuracy is better than ±60 ns with 99% probability according to the specifications of the GPS chipset. The time stamping method described above results in time stamping accuracy within the sub-microsecond range, typically less than 100 ns.

Given such an accurate technique of applying time stamps, the error of actual sampling clocks vs. the GPS time base, can be analyzed. An ADC requires a clock with a specific oscillator frequency to drive its sampling. Environmental factors like temperature changes can cause an ADC clock drift.

Besides the short-term drift, the ADC sampling clock - which is driven by an internal oscillator in the hardware - may have an inherent offset compared to oscillators on other CoCo units or compared with the atomic clocks used by GPS time. The combination of offset and drift produces a bias of the clock. For a recording time of a few minutes this bias may not be a major problem. However, if the recording time is as long as hours or days, this sampling clock bias may cause sampled data from different units to have mismatches when comparing time stamps.

Fig.16 Time difference caused by inaccurate nominal sampling rate

After using the time stamps that are carried over in the acquired vibration data, the sampled points can be lined up on the plot.

Fig.17 Synchronized time signals after applying first order correction

The result is that signals collected at different times and locations can be accurately synchronized post-acquisition, enabling comprehensive analysis across distributed systems. This capability is particularly valuable for structural health monitoring and operational modal analysis, where data from various points of a large structure must be merged and analyzed as a coherent set to assess vibration and dynamic properties effectively.

3. Windowing

Windowing is an important signal processing technique applied to a time-domain signal before conducting a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). When a signal is sampled for FFT, it is assumed to be periodic within the sampled interval. However, if the signal is not periodic within this interval, the FFT assumes that there is a discontinuity at the boundaries, leading to spectral leakage. Spectral leakage manifests as spurious frequency components in the spectrum that obscure the true frequency content of the signal.

The Hanning window (sometimes called the Hann window) is used to taper the edges of the signal smoothly to zero, reducing the discontinuities at the boundaries. This tapering minimizes the leakage by reducing the abrupt changes at the start and end of the sampled segment.

The mathematical expression for the Hanning window w(n) is:

n is the sample index, ranging from 0 to N - 1

N is the total number of samples in the window

When applying the Hanning window to a signal 𝑥[𝑛], the windowed signal 𝑥w[𝑛] is defined as:

This equation indicates that each sample of the original signal 𝑥[𝑛] is multiplied by the corresponding value of the Hanning window w(𝑛). The result is a modified version of the signal where the amplitudes near the boundaries are reduced to zero, creating a smoother transition at the edges.

Fig.18 Diagram showing the Hanning Window

This results in a cleaner, more accurate frequency representation after the FFT. The Hanning window is particularly suitable for analyzing random signals or signals with non-periodic components because it effectively smooths the data.

4. FFT and Correction

The Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) and the associated correction factors are used to ensure that the frequency domain representation accurately reflects the time-domain data. FFT is a fundamental tool in signal processing, allowing for the transformation of a time-domain signal into its frequency-domain representation. This transformation is crucial for modal analysis, as it helps identify the dominant frequency components in a structure's vibrational response.

The FFT is an efficient algorithm for computing the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT), which converts a discrete time-domain signal into its frequency-domain components. The DFT of a signal 𝑥[𝑛] with N samples is given by:

- X[K] is the complex-valued frequency component at index K

- xw[n] is the windowed time-domain signal

- j is the imaginary unit

- N is the total number of samples

- k ranges from 0 to N-1 and corresponds to discrete frequencies

The result X[K] contains both magnitude and phase information of the frequency components. The magnitude spectrum |X[K]| provides information about the amplitude of the sinusoidal components, while the phase spectrum ∠X[K] indicates the phase shift at each frequency.

Fig.19 Diagram illustrating the FFT process

To ensure that the frequency-domain representation accurately reflects the characteristics of the original time-domain signal, correction factors are applied after the FFT:

Amplitude Correction: The FFT results must be scaled to represent the true amplitudes of the frequency components. This correction accounts for the fact that the raw FFT output is scaled by , the number of samples. The corrected amplitude can be obtained by:

Energy Correction: This correction factor scales the FFT result by √N. This ensures that the energy content in the frequency domain matches the energy content in the time domain. Square root normalization is appropriate when analyzing power spectral densities and other energy-based metrics.

The FFT is an indispensable tool for frequency domain analysis, enabling the conversion of time-domain signals into their constituent frequencies with efficient computation. The application of amplitude and energy corrections ensures that the output is correctly scaled, preserving the accuracy of the spectral analysis.

5. CPS Calculation with Phase Correction and Post-Processing

This section explains how to correct the phase measurement based on GPS time stamps. The Cross Power Spectrum (CPS) is a frequency-domain measure used to evaluate the relationship between two signals, typically a reference signal x(t) and a response signal y(t). The CPS indicates how energy at a particular frequency is distributed between the two signals and helps identify correlated frequency components. It is calculated as:

- Sxy [K] is the CPS at frequency bin K

- X[K]and Y[K] are the FFTs of the time-domain signals x(t) and y(t), respectively

- Y*[K]denotes the complex conjugate of Y[K]

The CPS helps identify the shared frequency components between the two signals and is fundamental for determining the coherence and phase relationship at specific frequencies.

In OMA, CPS calculations are essential for identifying modes of vibration and assessing how different parts of the structure respond relative to each other. By analyzing the CPS, engineers can detect dominant frequencies and assess the energy transfer between the reference and response points of the structure, which aids in extracting modal parameters such as damping ratios and mode shapes.

A phase correction is applied to the CPS to account for any time delay between the different data acquisition systems. Sxy[K] is the instantaneous cross spectrum before averaging has been performed. This array contains N pairs of complex numbers and its nth element is Sxy[n]. After Sxy is calculated, a phase correction is applied to each point of the signal Sxy[n].

The recorded data from two input channels has a known time delay of dt, which can be derived from the two time stamps of each channel. The phase correction formula will apply the following phase change to each element:

dt is the time delay between the starting point of the block of X channel vs. Y channel, which are derived from the two time stamps of both channels

dT is the nominal sampling interval. For example, for a sampling frequency of 102.4 kHz the dT is 9.765625 µs.

n is the index number of the element in the array

N is the total size of the array

The formula indicates that if the time delay is 1 sample point long, the phase shift between two channels will be 2π, or 360 degrees, when the frequency index is equal to the sampling frequency. The following figure shows how it can be described in the frequency domain:

Fig.20 Phase shift illustrated in frequency domain

If the complex number is represented in terms of amplitude and phase, the phase correction can be directly applied to the phase component. However, if the complex number is expressed in real and imaginary parts, it must first be converted to its amplitude and phase representation, apply the phase correction, and then reconverted back to the real and imaginary form.

Averaging is applied to the phase corrected CPS to reduce noise and improve the stability of the frequency-domain representation. This process is particularly beneficial when dealing with real-world data, which often contains random noise and fluctuations that can obscure meaningful insights. The averaging of CPS over measurements is performed as:

is the averaged CPS at frequency bin K

is the averaged CPS at frequency bin K is the CPS for the ⅈth measurement

is the CPS for the ⅈth measurement- M is the number of measurements or segments over which the averaging is performed Averaging improves the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) by reducing the impact of random noise, leading to a more robust representation of the structural response.

Averaging improves the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) by reducing the impact of random noise, leading to a more robust representation of the structural response.

Scaling the CPS ensures that the power spectrum of each measurement point is consistent and comparable to the reference Auto Power Spectrum (APS). This approach corrects for variations in power levels across different measurement points or when environmental conditions change between measurements enabling consistent interpretation of modal data. The APS is an essential measure in signal processing that represents the power distribution of a single signal across different frequency components. The APS for a signal can be expressed as:

X[K]is the FFT result of the signal at frequency bin K

X*[K] is the complex conjugate of X[K]

To scale the Cross Power Spectrum (CPS) for measurement points using a reference APS, the scaling ratio is defined as:

This ratio compares the power of the baseline reference APS to the power of the current APS at the same frequency bin. It ensures that the CPS for different measurement points is proportionally adjusted relative to the reference APS.

The scaled CPS can then be computed using the following equation:

This approach ensures that each measurement's CPS reflects the power distribution relative to a consistent baseline, providing more accurate and reliable results in operational modal analysis.

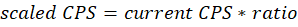

Fig.21 Magnitude and Phase representation of a CPS signal

Smoothing is applied to the CPS to further reduce the fluctuations and provide a clearer spectral representation. Smoothing helps mitigate sharp, random variations that do not represent the actual vibrational characteristics of the structure. A common method for smoothing involves using a 7-point approximation filter or 7-point moving average filter, by averaging the current data point with its three preceding and three succeeding points, which can be mathematically represented as:

S(i)is the smoothed CPS at frequency bin K

P(j)is the original value of the CPS at point j ranging from i-3 to i+3

Fig.22 CPS signal of a measurement point before smoothing is applied

Fig.23 CPS signal of a measurement point after smoothing is applied

This averaging process reduces sharp spikes and fluctuations in the CPS, resulting in a smoother curve that better represents the underlying frequency content of the signal.

6. Mode Indicator Function

The Complex Mode Indicator Function (CMIF) is a powerful tool used in modal analysis to identify the natural frequencies and modes of a structure. It is particularly effective when applied to the CPS matrix obtained from OMA, where multiple output measurements are taken under ambient or operational excitation.

With the steps described above, multiple measurements are taken across different points on a structure to capture its vibrational response. The CPS matrix Sxy is a collection of cross power spectra between pairs of reference and response signals:

- Sxiyj represents the CPS between reference xi and response yj at a given frequency bin

- m and n denote the number of reference and response measurement points, respectively

Fig.24 Multiple CPS signal overlaid

The CMIF is derived by performing Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) on the CPS matrix for each frequency bin K. The SVD decomposes the CPS matrix as follows:

- U[K]and V[K] are unitary matrices representing the left and right singular vectors, respectively

- Σ[K]is a diagonal matrix containing the singular values σ1 [K],σ2 [K],…,σr [K] at a given frequency bin K

- VH [K]is the Hermitian transpose of V[K]

Fig.25 CMIF plot indicating modes from the CPS matrix

The CMIF is defined as the plot of the singular values σi [K] across all frequency bins K. The peaks of these singular value curves indicate the presence of modes, as they correspond to frequencies at which the structure exhibits strong vibrational energy.

The use of the CMIF, derived from SVD, helps separate true modes from noise and artifacts in the data. CMIF can simultaneously highlight multiple modes present in the structure. The function provides a clear and intuitive method for identifying natural frequencies by visually analyzing singular value peaks.

7. Modal Parameter Extraction

Curve-fitting is the process of applying mathematical models to data points to identify specific characteristics—in this case, the modal parameters of a structure from the CMIF data. The Poly-X method is a sophisticated algorithm used to fit the CMIF data to extract these modal parameters, such as natural frequencies, damping ratios, and mode shapes.

The Poly-X method, also known as the Poly-reference least-squares complex frequency-domain (p-LSCF) method, is a high-resolution technique for curve-fitting frequency response functions. It is particularly effective for operational modal analysis due to its robustness in handling noise and complex systems.

In the p-LSCF method, the system's response in the frequency domain is represented using a polynomial model. This model relates the response outputs to an unknown input which is inherent in OMA. The characteristic polynomial A(z) is used to express the system's behavior, where z is a complex exponential representing the discrete frequency variable:

ω is the angular frequency

T is the sampling period of the data

The polynomial is expressed as

This polynomial has coefficients ai that is determined through the curve-fitting process.

The goal of curve-fitting in the p-LSCF method is to find the polynomial A(z) such that the roots (or poles) of this polynomial match the dynamics observed in the CPS matrix. The CPS matrix Sxy(ω) contains cross power spectral information that reflects the correlations between the responses at various points on the structure. By fitting a polynomial model to this matrix across frequency bins, we can identify the frequencies at which the structure has significant vibrational energy, corresponding to the natural frequencies.

The curve-fitting step involves minimizing the difference between the polynomial representation of the system and the actual CPS data. This is done by solving a least-squares problem:

is the modeled CPS data based on the polynomial

is the modeled CPS data based on the polynomial- M is the number of frequency bins

To perform this curve-fitting, the least-squares approach is used to find the coefficients a1, a2,…, an of the polynomial A(z). These coefficients define the polynomial that best fits the CPS data over the frequency range analyzed. The fitting process can be visualized as finding the set of coefficients that minimizes the error between the actual CPS matrix values and the values predicted by the polynomial model.

After the polynomial A(z) is determined, its roots (poles) are calculated:

Where zi are the complex roots of the polynomial. The locations of these poles in the complex plane reveal the modal properties:

The frequency of the mode which can be represented as

The damping ratio of the mode which can be represented as

The results of the curve-fitting process are displayed in a stability diagram, where the poles identified across different model orders are plotted.

Fig.26 Poly-X Stability Diagram

Poles that consistently appear in multiple model orders are considered true modes, while others that vary significantly are treated as noise or computational artifacts.

Fig.27 Modal Parameters of test specimen

The mode shapes of the mode can be derived from the left singular values of the CPS data .

Experimental Workflow

An experimental test was conducted on a full-scale five-story building (270 x 70 x 100 feet) to evaluate a GPS-based Operational Modal Analysis (OMA) methodology. This approach integrates GPS timestamp technology with distributed handheld data acquisition systems to ensure precise synchronization across multiple sensors, enabling efficient monitoring of the building's dynamic response under ambient conditions.

The process begins with strategically placing 124 measurement points across the building’s critical structural elements, mapped onto a 3D geometric model. This model segments the building into north, south, and overhang sections, ensuring comprehensive vibrational response coverage.

Next, a test plan is prepared and uploaded to CoCo-80X handheld systems. These rugged, portable devices facilitate real-time field data collection. Specific CoCo units and sensors are assigned: one unit captures reference sensor responses, while two additional units manage 14 roving sensors measuring acceleration in the X and Y directions. GPS antennas provide precise time synchronization.

Fig.28 Experimental Workflow Chart

Data acquisition occurs in 18 runs of approximately 10 minutes each, with raw timestream data recorded at specified points. Sensors with a sensitivity of 10 V/g are securely mounted for accurate measurement. The collected data is then merged and synchronized using GPS timestamps. Signals are processed to correct sampling rates, and FFT settings (3600 spectral lines, Hanning window, linear averaging) are applied for high-resolution frequency domain analysis. Post-processing includes phase correction, averaging, scaling, and smoothing to minimize noise and variability.

Modal parameters are extracted by curve-fitting the processed data using the Complex Mode Indicator Function (CMIF) and the Poly-X algorithm with the p-LSCF method. This analysis identifies natural frequencies and damping ratios, with the first bending and torsion modes measured at 1.741 Hz and 2.034 Hz, respectively.

This methodology demonstrates the practicality and effectiveness of GPS-synchronized handheld systems for structural health monitoring and modal analysis, offering precise insights into dynamic building behavior for civil engineering applications.

1. Measurement Layout and Sensor Deployment

The systematic approach described below is used for designing the measurement point layout to capture the dynamic response of a full-scale building under OMA. This strategy ensures comprehensive spatial and geometric coverage, enabling accurate identification of the building’s mode shapes and other dynamic properties.

Fig.29 Building on which the OMA test was conducted

Vibrations are measured at critical structural locations—specifically along the building's columns. These columns serve as the primary load-bearing elements, making them ideal points for observing how the structure responds dynamically to ambient excitation. By focusing on these key areas, the layout ensures that the collected data captures the structural behavior most representative of the building’s overall response.

The measurement layout divides the building into three distinct regions: the north, south, and overhang portions. Each region is modeled separately to ensure that all structural components are accounted for during the data collection process. This segmentation improves spatial resolution by targeting specific areas where localized modes may occur while still maintaining the global response characteristics.

Fig.30 Highlighted measurement points on the columns of the building floor plan

To maintain consistency, the same measurement grid is replicated across every floor of the building. This uniformity ensures that the vertical dynamics are captured with precision and that no floor is underrepresented in the analysis. Each floor's measurement points align with the points directly above and below, forming a three-dimensional grid of data collection points that span the entire height of the building.

2. 3D Geometric Modeling

This process transforms the spatial coordinates of measurement points into a detailed wireframe model of the structure. By using a systematic bottom-up approach, the geometry creation ensures that every structural component of the building is accurately represented, forming a solid basis for analyzing its dynamic behavior.

The x, y, and z coordinates of all the measurement points are entered into the geometry creation tab of the EDM Modal Software. These coordinates represent the precise physical locations of the sensors deployed during the OMA test. By including every measurement point, this step ensures that the model is fully aligned with the experimental data collected from the building.

Fig.31 Each component of the building modelled using the bottom-up approach

The geometry model is built using a bottom-up approach, starting from the foundation and progressing incrementally to the roof. This method models each floor as a separate component, making it easier to handle the complexity of the building’s structure.

After all measurement points are defined, they are systematically joined using lines to create a wireframe representation of the building. This wireframe provides a structural visualization of the relationships between the columns, floors, and building sections to reflect logical connections and comprehensive coverage of the building.

Fig.32 3D geometric model of the building

The entire geometry creation process is performed within the geometry tab of the EDM Modal Software. This tool facilitates the input, organization, and connection of measurement points into a cohesive model.

3. Test Plan Development

The structured approach to data collection during the OMA test, detailing the roles of CoCo handheld devices, accelerometers, and GPS antennas is outlined here. This carefully planned methodology ensures precise, synchronized data collection and comprehensive coverage of the building’s measurement grid.

Three CoCo handheld devices are utilized for data acquisition, each assigned a specific role to streamline the collection process. One CoCo is dedicated to collecting data from a fixed reference accelerometer, which measures vibrations in both the X and Y directions at a predefined location on the building. This reference point provides a stable baseline against which all other measurements are synchronized and compared. Two additional CoCo devices are deployed to record data from 14 roving accelerometers (7 accelerometers in the X direction and 7 accelerometers in the Y direction). The roving accelerometers are repositioned systematically to span the entire measurement grid. This approach enables the capture of vibration data across all critical structural points while minimizing the number of test runs required.

Fig.33 Schematic of the building with CoCos laid out for data collection

Each CoCo device is equipped with a GPS antenna to ensure precise time alignment of the recorded data. A total of 3 GPS antennas are used—one per CoCo device. These antennas record timestamps for every acceleration measurement, enabling accurate synchronization across all devices, even when they operate independently. This temporal alignment is crucial for merging data during post-processing.

Fig.34 GPS enabled on CoCo for recording time stamp

A comprehensive test plan is generated to coordinate the movement and data collection process. The test plan leverages the 3 CoCo devices and specifies the use of 14 channels for roving accelerometers during each step of the measurement process. The roving step size is set to 7 channels, ensuring that the measurement grid is fully covered across all runs. This method allows the accelerometers to systematically move to new positions while maintaining coverage and resolution.

Fig. 35 Test plan for each device based on measurement point locations

The sampling rate for all CoCo devices is set to 125 Hz. This value is chosen based on the frequency range of interest for the building, which is approximately 50 Hz. The selected sampling rate satisfies the Nyquist criterion, ensuring that all relevant frequency content is captured without aliasing. This configuration provides sufficient resolution to analyze the building’s dynamic response accurately.

The combination of a well-defined test plan, GPS-synchronized CoCo devices, and a systematic roving strategy ensures efficient, accurate, and comprehensive data collection for the OMA test. This setup provides a robust foundation for analyzing the building’s modal characteristics and dynamic response.

4. Data Acquisition

The detailed test plan and configuration used for data collection during the OMA test is elaborated here. The integration of the test plan with the CoCo devices and the geometric model ensures precise data collection while optimizing setup efficiency and time.

The test plan, along with the geometric model of the building, is uploaded to the CoCo devices prior to the test. The test plan specifies the operational details for data collection. It identifies which CoCo device should be positioned at each location to record data from the corresponding accelerometers. The plan ensures that the data collection is systematic and aligned with the pre-designed measurement grid, facilitating smooth execution of the test runs.

Fig.36 Setting up accelerometers on the mounting block at the measurement location

For accurate and reliable data collection, X and Y uni-axial accelerometers are mounted together at the same location. A mounting block is used to securely hold the two accelerometers, enabling them to collect bi-directional data (in both the X and Y directions) from a single measurement point. This configuration ensures precision in capturing the building’s vibrational response across both axes, which is critical for accurate modal analysis.

Fig.37 Recording raw measurements on the CoCo data acquisition system

The accelerometers used in the test have a sensitivity of 10 V/g, allowing them to detect even subtle vibrations caused by ambient excitations such as wind and traffic. This high sensitivity ensures that the sensors can accurately capture the building’s dynamic response under operational conditions.

Fig.38 Zoomed in picture of the accelerometer and mounting block setup

To minimize the time required for setup and data collection, 100 ft cables are employed along with the multiple CoCo devices. These long cables allow the accelerometers to cover a large area of the building from a single CoCo device placement, reducing the number of test runs needed. The configuration optimizes the balance between efficient data collection and ensuring full coverage of the building’s measurement grid.

Fig.39 Picture showing the deployment of sensors and CoCo systems on the roof of the building

The integration of a well-designed test plan with the CoCo devices and geometric model, combined with precise sensor configuration and GPS synchronization, provides a robust and efficient framework for data collection.

5. Data Processing

This section outlines the critical post-processing steps that follow the completion of data collection during the OMA test. This stage involves transferring, synchronizing, and processing the data to prepare it for frequency-domain analysis. The seamless integration of GPS timestamp technology with advanced computational techniques ensures the accuracy and reliability of the processed results.

After the measurement runs are completed, the raw acceleration data recorded by the physically disconnected CoCo devices is transferred to the EDM Modal Software on the PC. The software acts as a central platform for organizing, synchronizing, and processing the collected data.

The synchronized time-domain data is converted into the frequency domain to facilitate modal analysis. FFT is applied to acceleration data, generating frequency-domain signals, including the CPS. To achieve fine frequency resolution, the FFT is configured to use 3600 spectral lines. This ensures that the frequency range of interest, particularly around the building’s natural frequencies, is captured with high precision.

Fig.40 Picture illustrating post-processing of the time domain data

Several advanced signal processing steps are applied to enhance the quality and usability of the frequency-domain data. A Hanning window is applied to the random acceleration data to reduce spectral leakage, as described earlier in the theory section. Phase correction is applied to the computed CPS data. Linear averaging is performed across multiple runs to reduce noise and variance in the frequency-domain data, as previously detailed in the theoretical framework.

An important step in the post-processing workflow is scaling the CPS. The measured CPS values from different locations, floors, and environmental conditions are scaled relative to a baseline reference CPS.

The DOFs, which include information about the measurement point and the direction of the accelerometer (X or Y), are seamlessly recorded in the test plan of each CoCo device during the data acquisition phase. During post-processing, this information is cross-referenced with the test plan on the PC to ensure that all data is correctly organized and labeled. This automated logging eliminates errors and streamlines the data analysis process.

Fig.41 Screenshot illustrating automated logging of recorded data and computed data

The post-processing workflow described above ensures that the raw acceleration data collected during the OMA test is transformed into high-quality, synchronized, and organized frequency-domain data.

6. Modal Analysis

This section describes the crucial steps taken to analyze the post-processed CPS data, ultimately leading to the extraction of the building’s natural frequencies, damping ratios, and mode shapes. This process involves a sequence of operations, including smoothing the CPS matrix, performing SVD to generate a CMIF plot, and curve-fitting the results using the Poly-X method to extract the modal parameters of the building.

The first step in analyzing the CPS matrix involves applying a smoothing operation to mitigate noise, sharp peaks, and fluctuations present in the frequency-domain data.

Fig.42 Picture showing the overlapped CPSs

After the CPS matrix is smoothed, SVD is applied to extract dominant modes and visualize them using a CMIF plot.

Fig.43 CMIF plot after applying SVD to the CPS matrix

After identifying the dominant modes using the CMIF plot, the Poly-X method is used for curve-fitting to extract precise modal parameters.

Fig.44 Stability diagram with Poly-X method

The singular vectors from SVD are combined with the identified poles to compute the mode shapes, describing how different parts of the building vibrate at each natural frequency.

Fig.45 Bending mode of the building at 1.74 Hz

First Bending Mode at 1.741 Hz: Representing lateral displacement.

Fig.46 Torsion mode of the building at 2.03 Hz

First Torsion Mode at 2.034 Hz: Indicating torsional response.

The analysis of the CPS matrix through smoothing, SVD, and curve-fitting forms the backbone of modal analysis in OMA. The application of these techniques ensures that the extracted natural frequencies, damping ratios, and mode shapes are reliable and representative of the building’s actual dynamic behavior. This comprehensive process provides critical insights into the structural health and vibrational characteristics of the building.

The results demonstrate the system’s ability to capture accurate modal data, which is vital for SHM programs aimed at early damage detection.

Conclusions and Future Decisions

This comprehensive study validated the efficiency and reliability of distributed handheld systems with GPS synchronization for OMA. The capability to identify significant modal properties without extensive wiring or manual data alignment marks a significant advancement. Future research could extend this methodology to more complex structures, incorporating automated excitation systems for higher-order modal analysis.

Fig.47 Pictorial illustration of an OMA test on bridge with some results

References

Inman, Daniel J., “Engineering Vibrations, Second Edition,” Prentice Hall, New Jersey, 2001.

Bart Cauberghe et al. “The secret behind clear stabilization diagrams: the influence of the parameter constraint on the stability of the poles”. In: Proceedings of the 10th SEM international congress exposition on experimental and applied mechanics. 2004, pp. 7–10.

Sanjit K. Mitra and James F. Kaiser, Ed. Handbook for Digital Signal Processing, Wiley-Interscience, New York, 1993.

James Zhuge, US Patent #11,956,744, granted on 4/9/2024, Sampling Synchronization through GPS Signals.

James Zhuge, US Patent #11,754,724, granted on 9/12/2023, Cross Spectrum Analysis for Time Stamped Signals.